Chestnut Article

This is a rough Copy of an article I wrote for the Quarterly Journal of Forestry. The article actually contains more Photos.

If the Romans Did Not

Bring Sweet Chestnut to

Britain, Who Did?

John Pitcairn looks into this intriguing question following a

throwaway remark at the 2023 Whole Society Meeting.

At the recent excellent Whole Society Meeting hosted

by the South Eastern Division, we saw exemplary

sweet chestnut coppice silviculture and were

introduced to its economic and cultural importance. At

one estate the host, in an almost throwaway remark, said

that a Dr Robin Jarman had made a convincing case for

the Romans not being responsible for the introduction of

sweet chestnut into Britain and that the first evidence for

it was from the 6th or 7th century. This, according to my

schoolboy history, was when the Jutes, Angles and Saxons

arrived from Denmark and northern continental Europe.

These are not areas I associate with sweet chestnut, and

a Roman introduction seemed more likely to me. I realised

I had no idea what evidence there might be and decided

to do some research online. It was an interesting idea to

explore and focussing on papers that were freely available

I quickly located and downloaded a thesis ‘Sweet chestnut

(Castanea sativa Mill.) in Britain: a multi-proxy approach

to determine its origins and cultural significance’ by Robin

Andrew Jarman (Jarman, 2019). I did read all 57 pages

of text but not necessarily the seven pages of references!

I thought readers might appreciate a summary of what I

discovered.

Fortunately, the introduction did explain the importance

of determining the date of sweet chestnut’s arrival, which

I thought interesting but unimportant. Whether sweet

chestnut is indigenous, an archaeophyte (an ancient

introduction) or a neophyte (a modern one) is a significant

question. The question relates to its naturalness, a key

function in the Nature Conservation Review 1977 which

determines which species should be protected or regarded

as invasive; this might become relevant should sweet

chestnut blight take hold in this country.

The aim of the thesis was to determine:

When is the earliest verified date for sweet chestnut

growing in Britain?

Whence do the longest-established British sweet

chestnut trees derive?

Does new evidence for antiquity and origins alter the

ecological and cultural significance of sweet chestnut in

Britain?

|

King’s Wood near Worksop, Sherwood Forest, Sweet Chestnut originally planted

by the Dukes of Portland. |

I shall just cover the parts relevant to sweet chestnut’s

arrival and any information as to where it may have come

from, considering what the evidence is and why Dr Jarman

cast doubt on it. The debate on the origin of British sweet

chestnut has a long history. John Evelyn considered it

non-native and in his 1706 4th edition of Silva suggested a

Roman introduction. This became

the consensus view of the Royal

Society in the 18th century but

lacked evidence.

Oliver Rackham believed

sweet chestnut to be a Roman

import, or so I thought. Dr Jarman

reveals he worked with Rackham on and off from 1971, and

that Rackham had reservations about the species being

a Roman introduction. The idea was being quoted and

requoted in an academic echo chamber without the primary

evidence being checked. It became a ‘factoid’ as Rackham

called it (something everyone believes but is not, in fact,

true). As I am taking what Dr Jarman has written at face

value, I may be contributing to a new ‘factoid’! Dr Jarman

has tried to re-examine original archaeological material

and interview the researchers. He also visited semi-natural

woodlands as well as ancient chestnut trees both alive and

dead, to establish its cultural and social significance.

A literature review was undertaken, and archaeological

archives were reviewed looking for pollen, charcoal, nuts,

and timber references prior to 1350 AD. An attempt was

made to locate all recorded archived specimens up to

650 AD and to re-evaluate their authenticity with modern

techniques. This was carried out in partnership with English

Heritage.

The thesis was essentially a summary of a number of

previously published papers that

Dr Jarman had been involved

with, usually as lead author.

The thesis is divided into four

sections: (1) archaeological

records, (2) dendrochronology,

(3) genetics, and (4) historical

ecology. What follows is my understanding of the key points

Dr Jarman makes grouped into ‘archaeological records’

and then a combination of the last three sections of his

thesis.

Archaeological records.

Dr Jarman located 35 archaeological records of archived

sweet chestnut material from before 650 AD, i.e. the

Roman and post-Roman period. He tried to find and

re-examine them physically. For me, the most striking

finding was that there were no confirmed records of sweet

chestnut pollen prior to 650 AD.

There were only two reports of archaeological records

of sweet chestnut nut fragments in the pre-medieval

period. One was from an excavation at Great Holts

Farm in Essex in the 1990s. The find consisted of five

fragments of chestnut pericarp found in a Roman well that

had been filled with rubble and rubbish. The waterlogged

bottom of the well contained organic material including “a

few fragments of sweet chestnut nut pericarps, walnuts,

hazelnuts, olive stones, grape pips, stone pine nuts,

cherry stones, sloe, bullace and apple pips.” Some of

these items must have been imported, for what looks like

feasting. This cannot be considered good evidence for

a local source of chestnuts, not that it had been claimed

to be. The other reported sample, from Castle Street in

Carlisle, was radiocarbon dated to a much later period.

Reports of the sweet chestnut charcoal remains

also proved problematic, in part because many of the

recorded archived pieces could not be located. There

was also a degree of misidentification. Samples recorded

as sweet chestnut turned out to be ash or alder, but

mainly oak. Small pieces, particularly small branch

wood, may be indistinguishable from oak. Oak can

confidently be distinguished from sweet chestnut by the presence of multiseriate medullary rays. The problem is

that the absence of rays particularly in a small fragment

is not proof it is chestnut. Creating fresh surfaces for

examination was not possible due to the importance of

the specimens. The dating of some samples could not

be verified or was confirmed to be inaccurate. Some key

samples were from 19th century excavations and their

accounts had been regularly requoted but had not been

questioned. Reported wood and wooden artefacts were

confirmed; however, a writing tablet

or a tool handle could easily

have been imported.

There are waterlogged

chestnut stakes and

piles from the Alverstone

Marshes on the Isle of

Wight, which have been

carbon dated to the 6th and

9th-10th century, but this study had not been published

when Dr Jarman put his thesis together in 2019.

There is a possible sweet chestnut pollen grain from

Uckington, Gloucestershire that is dated to the 7th

century. This with the Alvestone Marshes wood could be

the only physical evidence of sweet chestnut products

that could have been derived from plantations established

in the Roman period. In summary, no definitive archived

material could be found to confirm locally grown sweet

chestnut in England and Wales during the Roman and

immediate post-Roman period.

|

| Sweet chestnut regenerates freely. |

Historical ecology/genetics/

dendrochronology.

The earliest written record for growing sweet chestnut

is in the 12th century (1113 AD), from legal ecclesiastic

documents near the current Forest of Dean. It must, therefore,

have been established in the 11th century at the latest.

There are a number of large ancient sweet chestnut

trees on estates and in former deer parks, some shown to

be more than 400 years old. Dendrochronology does not

take any sweet chestnut back more than a few hundred

years; DNA analysis has confirmed ancient clonal coppice

stools but provides no date. DNA might provide evidence

for where introduced sweet chestnut originated and so

provide clues to who introduced it. DNA analysis has

been carried out on British and Irish sweet chestnut for

comparison with European records.

Sweet chestnut along with other flora retreated to refugia

ahead of the ice sheets of the Ice Ages.

Three refugia

genepools have been identified. An eastern (E. Turkey

and the Caucasus), a central (W. Turkey, Greece and part

of the Balkans), and a western (Italy, Spain, Portugal and

southern parts of France and Switzerland). DNA samples

from England and Wales are from the western area but they

represent two separate genepools. These genepools are

geographically mixed, suggesting at least two substantial

introductions. The older British DNA samples showed some

commonality with samples from Portugal to Romania. It is

a diverse genepool but whether that is because of multiple

introductions or because of mixing on the continent prior

to introduction cannot currently be

determined. Ancient parkland trees

usually came from NW Iberia

while plantations <200 years old

were more likely to be Italian;

one can imagine members of

the gentry returning from their

grand tour with pockets full of

chestnuts!

Sweet chestnut does not inform British myth or legend

but is often planted in parks or gardens in significant

places. It is of considerable economic and practical

importance. One of the reasons for calling sweet chestnut

an ‘honorary native’ is that it forms ecological associations

within semi-natural woodlands, which have been stable for

hundreds of years. They are also similar to forest vegetation

associations on the continent.

My initial reaction to the lack of pollen evidence may

have been misplaced. British sweet chestnut pollen

samples are very rare from the whole medieval period,

Sweet chestnut produces viable seed and naturally regenerates.

“If the Romans made

a concerted effort to introduce

sweet chestnut, there is evidence

they failed!”

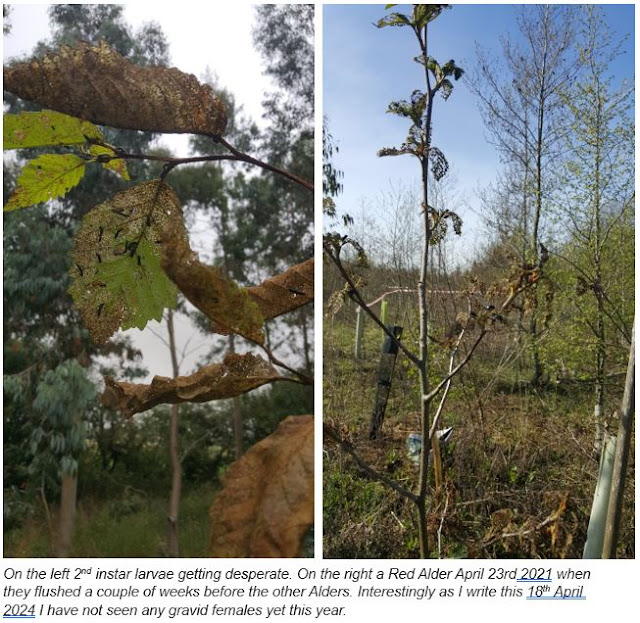

The area next to the willow coppice. which was predominately 3/4 rows of ash and 1/2 rows of Italian Alder and Hornbeam, was pollard felled in autumn 2025 has been replanted. 200 Oaks and about 85 hornbeam have been planted including an alternating streamside row which almost goes as far as the end of the plot opposite the dyke to the Old North Road. Photo is of pollarded Ash at Weston end of area, when first cut in the late summer 2024. This area planted in the autumn has been badly affected by voles eating through the base of the oak saplings. There will need to be beaten up.

The area next to the willow coppice. which was predominately 3/4 rows of ash and 1/2 rows of Italian Alder and Hornbeam, was pollard felled in autumn 2025 has been replanted. 200 Oaks and about 85 hornbeam have been planted including an alternating streamside row which almost goes as far as the end of the plot opposite the dyke to the Old North Road. Photo is of pollarded Ash at Weston end of area, when first cut in the late summer 2024. This area planted in the autumn has been badly affected by voles eating through the base of the oak saplings. There will need to be beaten up.